Drawings made by fire and torch light with bats flying overhead. Tiles and oak box made with manual labour in mind. “I’m prospecting but what is it I’m searching for? Success? Wealth? Meaning? Glistening sheep droppings catch my eye. Is this what I have been looking for? I pick up a handful and put them into a plastic bag.

The tithe barn holds the light in a different way. Distracted by thoughts of Vermeer I look closely at the chipped and plugged wall behind The Milkmaid (c1660): on the floor a small open-fronted box with vents in the top holds an unknown object; behind the box, painted Delft tiles form a skirting board that shows human forms in motion.” SLD

The milkmaid’s room (box) European Oak / Pigment / Ceramic / 2017

The milkmaid’s room (tiles) Painted ceramic tiles (x9) / 2017

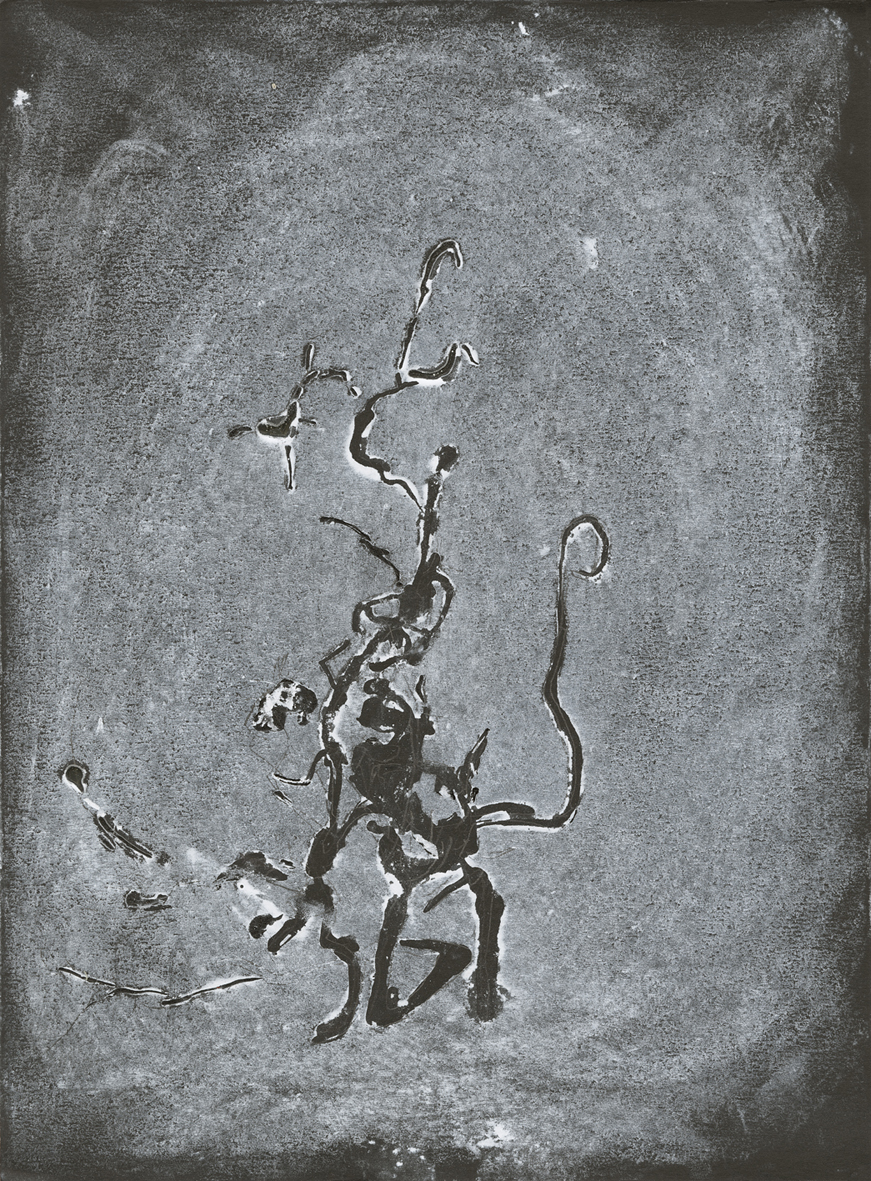

In this world of shit, baby you are it (3m x 4m)

Climbers’ chalk, ink and acrylic medium on paper / 2017

In this world of shit, baby you are it – detail

Torch light drawing #1 / Framed drawing (30cm x 20cm)

Climbers’ chalk on paper / 2015

Review by Trevor H Smith – October 2017

Simon Lee Dicker works with and within nature, to produce work that unravels the stories we attach to place and time, and the emotional weight that we impart upon them.

Dicker’s practice has spoken about a distance between humanity and nature, while producing work that facilitated the journeys of others and told their stories as they navigated their own relationships with location and landscape. These mediated methods of production have been supplanted by a more direct approach to his subject, through a distinctly hands-on form of making that incorporates drawing, painting, and woodworking to reveal significantly more of the artist’s hand in the work.

The focus of the work remains that passionate but slightly strained relationship between humanity and the natural environment, as emphasised by a series of three artist residencies undertaken on the island of Hoy and Papay, in the Orkneys. From a bothy at the northernmost extreme of the British Isles, overlooked by some of the UK’s highest cliffs, Dicker’s practice, which had been filtered through audio-visual recordings, large-scale digital prints, and his curatorial project, OSR Projects, underwent a physical re-grounding. From sparse materials a method was found; the island of Hoy is famous for its sea stack, the Old Man of Hoy, which is a popular climbing destination, and so climber’s chalk became a viable material for making work.

Back in Somerset, on a 24-hour residency in Cotley Tithe Barn, this method was repeated and refined. At night by the light of his headtorch, accompanied only by his and the barn’s resident bats, Dicker set about getting his hands dirty, searching for connections that would give the work further meaning. Having initially wandered the surroundings of the barn’s remote location in the Blackdown Hills on the Somerset-Devon border, Dicker settled on that often overlooked detail that one constantly encounters in open country – sheep’s droppings. The resulting artwork ‘In This World of Shit, Baby You Are It’ is huge in scale and presumably impossible to have made without crawling across and leaving all manner of unplanned markings on its surface. When hung it rises to the height of the tithe barn wall; its background is mottled, textured like worn leather, and dusty, while its detail bears a striking resemblance to its subject. The low autumn-afternoon sun streams through a narrow a window opposite, picking out and illuminating the black droppings in sequence as one moves through the space.

Accompanying this work is Milkmaid’s Room, a collection of works inspired by the light from that very window. Taking its title from Johannes Vermeer’s painting ‘The Milkmaid’ (c.1660), a famous example of Vermeer’s stock-in-trade side-lit effect, The Milkmaid’s Room comprises two elements; the first is a series of small ceramic tiles, each hand-painted with delicately rendered monochrome illustrations depicting the various forms of manual labour that have taken place on the Cotley estate over the centuries. Their blue ink could be the same blue that occupies almost a quarter of the canvas on Vermeer’s painting. The second element to Milkmaid’s Room is a small wooden box, measuring approximately a foot in all directions. Dicker’s same eye for detail that marked out sheep’s droppings as worthy of monumentalising is again at play here as he picks an overlooked element of the Vermeer painting and recreates it himself. In the bottom right hand corner, on the floor by the wall behind the milkmaid’s back, sits this box which, as it turns out, is a foot warmer. Dicker built his version from the same European Oak wood that the original would have been made from, and placed inside it not a red-hot glowing lump of coal as in the painting, but an amorphous hunk of clay covered in dry pigment, earth-red, which is also spread about the box directly on the floor of the barn, reflecting the manner in which the climber’s chalk has been used in the image that hangs nearby and its much smaller counterpart that was made up on Hoy.

This collection reveals an artist making connections with the past, through locations and the imagery they throw up, and through the provenance of linking subject matter and materials. The title of the exhibition at Cotley Tithe Barn is Propects, and prospecting is precisely what Dicker is doing – both within the landscape, in which he foraged for inspiration and to make the connections that start his conversation, but also within himself in this new way of interacting with his subject matter.

If working through mediating structures, such as audio-visual recording equipment, digital printing methods, and even curating the work of other artists, had put a distance between Simon Lee Dicker and his work, then this recent shift bridges that gap. There is a sense in the new work of an artist addressing a personal need to return to a physical medium, to get his hands dirty, and to play around a bit. Dicker, while maintaining his interest in that uneasy relationship between man and nature, has allowed himself the freedom to take chances – that his work is installed in a part of Cotley Tithe Barn that houses a wood-burning stove whose flue is almost as tall as ‘In This World of Shit…’ is high, only adds to the sense one has of the elements combining in Dicker’s favour. Indeed, assuming the stove to be a part of the installed work seems to be par for the course, and although he is quick to point out its pre-existing presence and purpose (the beaters gather round it at the end of the day to pluck the shooter’s quarry), Dicker is nonetheless delighted with the extra layer of meaning and purpose it imparts on the work. There is humour here, underpinned by the ever-present sensitivity one associates with the work of Simon Lee Dicker, and that warmth has been amplified by this new, tactile direction.